As I wander in the Camargue I am surrounded by swamps, bogs, marshes and estuaries. lakes, marshlands, salt marshes, and salt water lagoons (Etangs) as well as dunes, pools, grasslands, and forests.

Flamingos flame in the marshes while their young, still white, move in the tall reeds. Small bulls and white horses roam free in the horizon.

I am surrounded by a living and diverse organism. It is a dynamic system with a mind of its own that demands complex management. It is a system where one part inalterably affects another. It is vulnerable, beleaguered by its centuries of containments.

Despite centuries of anthropogenic activities the Camargue remains a vast expanse governed by the flow of saline and fresh waters with changing shapes and boundaries - with a will of its own as the pulsing flow of water carry sediments through its veins - its life blood.

Like other deltas the Camargue is a guardian at the gate and it needs protection.

The story of the Camargue and the efforts made there to bring people together through democratic processes with tools such as participatory research are important contributions to the question: how we are going to manage the uncertainties ahead?

Climate change is happening.

In 2021, unprecedented flooding around the world can be associated with the relative health of wetlands. Seas, rivers and lakes provide areas to store and slow the flow of water during floods and help steady flow rates, reduce flood peaks, and lower flood risks to towns and other infrastructure.

Currently, one percent of the globe are deltas and all are at risk along with the 500 million people who reside in these habitats.

Sixty to 80% of the world's wetlands have disappeared. In a number of cases the natural state of deltas have been replaced by artificial wetlands. These attempts at remediation happen for different reasons. Perhaps it is to improve agricultural lands, or to manage runoff or to improve water quality. Another reason might be to nurture wildlife. These are competing interests.

There is a timeline with climate change that pushes the need for cooperative solutions at local, regional, national, and international levels. For instance, the average sea level of Mediterranean region in general is expected to rise 3 feet by 2100. Many species have already been lost in the Camargue.

Manifestations of climate change is a planetary problem.

On its course for hundreds of years, the large Slims River in Canada's Yukon travelled northward toward the Bering Sea. In 2016, a receding glacier caused its waters to be diverted into a second river which ended up thousands of miles from the Slims River's destination. It had dried up in a matter of a few days rather than thousands of years. This event transformed the geological landscape. Researchers visiting the area discovered that what was originally a delta was now a dust bowl.

Glaciers are rapidly retreating almost everywhere around the world.

According to paleoclimate data the current warming is occurring around ten times faster than the average rate of ice-age-recovery warming. Carbon dioxide from human activity is increasing more than 250 times faster than it did from natural sources after the last Ice Age.

Whatever the events, cooperation demands a process to acknowledge the problem and to bring together diverse interests.

Conflicts because of competing needs is also a planetary problem. First, there must be viable food systems for expanding world populations. At the same time, our survival depends on preserving biodiversity as our only pathway to survival. This tension beleagers the planet.

The confluence of events that have occurred - floods, fires, the pandemic, political divisions, and the various other effects of climate change, have made the challenges of climate change more visible to more people in 2021 but also a polarized subject even as we run out of time. This adds up to a "wicked problem."

It is not that the answers are not there. They have been for centuries. It is, in fact, a matter of will even as the Camargue is reshaped in nature again and again by its nature and climate change realities. What will humanity do about climate change? Will there be an awakening? We look to stories for an answer.

The Camargue

The Rhone Delta system, the largest of four large delta systems in Europe, extends over 930km2 (2400 square miles) and opens up to the Mediterranean Sea. It is one of 33 other major deltas worldwide that represent critical habitats threatened by human activity, loss of biodiversity, and climate change.

The Camargue Regional Natural Park is (101,000ha or 390 square miles). The park was set aside in 1927 and granted National Park status in 1970. The Park is a rural territory with a mandate to balance natural areas with human activity. The Park is distinguished from the Camargue National Nature Reserve which is a protected natural space for the purpose of species conservation. Unlike the Park economic activities are not allowed.

Approximately a third of the Camargue is wetlands; lakes, marshlands, salt marshes, bogs, swamps, esturaries, and salt water lagoons (Etangs). Wetlands in the north dominate 84% of the natural environments.

The largest of the etangs, the Etang de Vaccares. is a saline lake is about 23 square miles and its deepest areas are around 2.5 feet deep. The large etang is the heart of water management in the Camargue. It is an important site for migratory birds, including the Greater Flamingo. In 1972 it was incorporated into the Camargue National Nature Reserve.

While Etang de Vaccares with its surrounding wetlands has been protected as a nature reserve since 1927, it continues to be exposed to pollution from nearby industrial parks and runoff from surrounding areas.

The Camargue is viewed as a natural and wild area and this is a draw for tourism. However, the dominance of private lands and human control has existed for centuries. This history has determined who benefits the most from the range, configurations, and movements of saline and fresh waters.

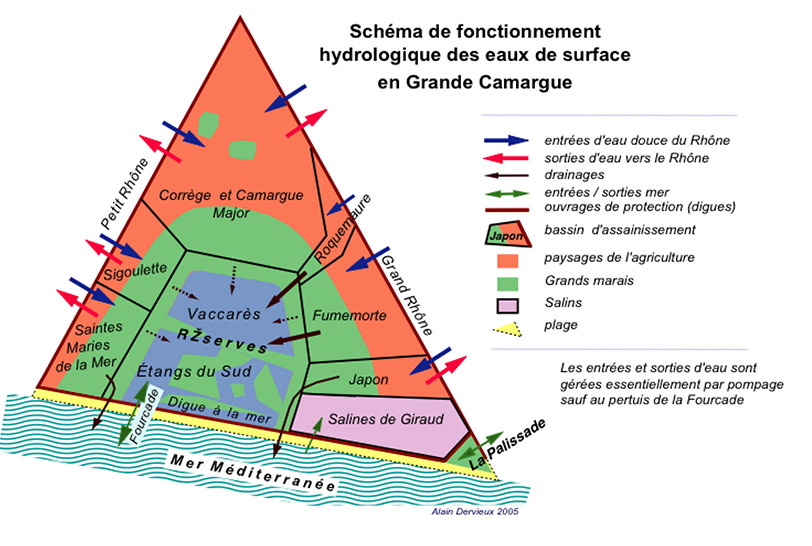

Generally speaking irrigation water is diverted to the north of the delta while sea water is introduced in the south for the production of salt. The degrees of salinity and fresh water runnning through the veins of the Camargue support wildlife niches and economic returns. Saline and fresh water diversions supplying interests representing industry, residents, and nature are controlled by valves. Water availability is seasonal and not always predictable. This is in line with socioeconomic concerns where conflicts between various industries and environmental mandates are primarily centered around uses of these waters for private and public use.

Participatory Research and stakeholders

So what we need above all is not new administrative structures, new repressive rules and laws, but a change in the heart of the people in order to build a consensus for moderate use and partitioning of the Camargue, and gradually to make nature a natural part of our cultural patrimony. That is to say, to realize that man is incomplete without nature, and to recognize that nature is a privileged area of reanimation for man. From this point of view the problem is no longer just to save the local economy of the Camargue, but to also save its cultural value. Once nature is considered by the people of the Camargue as vital in terms of culture as are the Arones or the Classical Theater of Aries, then the Camargue is saved. This is the end to achieve, not tonight or tomorrow but hopefully in the near future (A. Tamisier 1990).

Climate change affects the Camargue as it does generally on coastal environments. Increasingly, these environments have had significant species loss and are less secure for human habitation. This degradation has been happening for decades. It is now accelerated by the interplay of climate change and past anthropogenic interventions. Within the Camargue the unrelenting tide of economic demands and interferences have taken a toll on the delta before the Romans.

Adaptive management practices such as soft engineering and more inclusive participatory methods attempt to acknowledge the past and look to the will of the Camargue as not just containment but as a negotiation to be met not only through science but with the insights of indigenous knowledge.

Rice paddies are artificial wetlands and are water intensive. They are fed by the only irrigation system in the Camargue. The irrigation of rice requires desalinating soils with fresh water pumped from the Rhone River into the delta.

The paddies dominate vast lands in the Camargue that once were forests and grasslands. On the positive side the paddies provide habitat for wildlife. On the negative side rice produces the highest greenhouse emissions of all plant-based agricultural products, (Thompson 2021). Rice growing also calls for a heavy use of pesticides.

Due to the higher cost of rice and increasing demand the World Bank projects a sizeable increase in production to 555 million tons in 2035.

Rice is an important food globally. However practices have to change to balance biodiversity aims. This perspective incorporates symbiotic understanding. For example, grazing by manades (livestock) consisting of bulls and horses allows the development of a carpet of “saladelles” (sea lavenders). Sea lavender absorbs salt from the water and is a natural way of keeping water salinity in balance.

The salt marshes near Salin-de-Giraud in the southeast corner of the Camargue produce up to 15,000 tons of salt a day during the summer. *Salt, produced mainly along the final stretch of the Grand Rhône, is an industry that dates back to Romans times (first century AD). Salt-water intrusion, shallow water tables and degraded water reuse are dictated to by weather changes. This can have a negative impact on agriculture.

The Camargue has averaged around one million visitors a year. Invariably, the Camargue sell is a wild and free landscape along with cultural sights and interesting cusines. The impacts of tourism in the Camargue are complex. Tourism brings monetary benefits locally and to the government, as well as growth potential. On the other hand, there is no doubt about the damages caused by tourism. The revenue stream is valuable but it has a significant impact on ecosystems, including water use, and social structures. Climate change forces rethinking how to manage tourism better.

Participatory research

and "wicked problems"

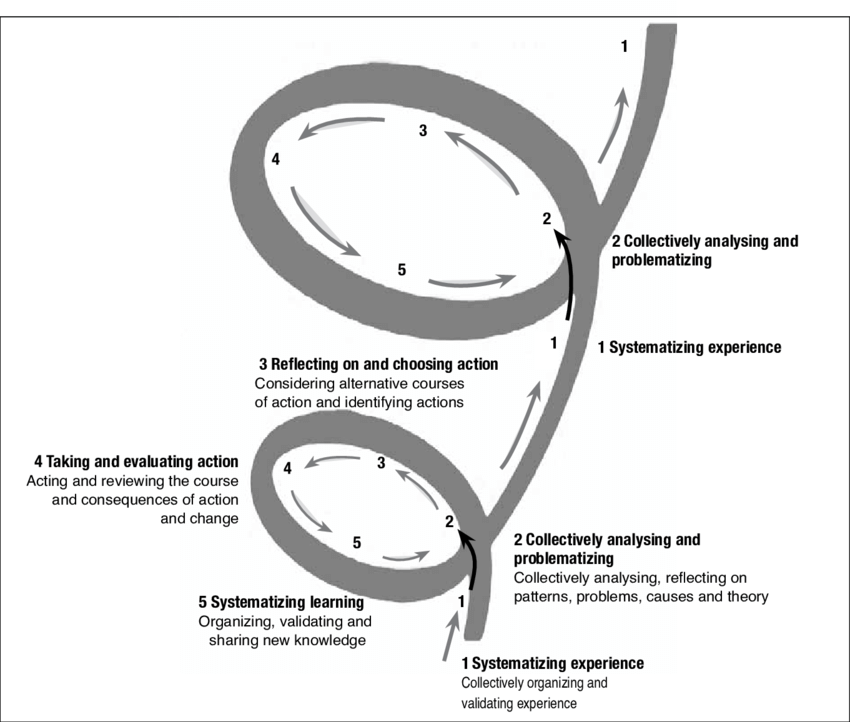

While an end game exists the focus of participatory methods is on process. This can be viewed as a spiral.

What about climate change? What are the particular challenges? Humans have social cohesion, innovation, imagination, and empathy in their bones. They also have fear and self-interests particularly in the face of unknown situations where they feel powerless. Climate change is something unforeseable and to be feared. It seems easier to draw inwards, maintain a status quo, and build a bulwark against all other interests.

As a response action research and participatory action research (PAR) methods have been used in the Camargue in efforts to draw in stakeholders, including the state, groups, organizations, and indigenous users, toward adaptive management practices. In cases this has been supported by government through emerging policies and programs.

Government and organizations have adopted methods that include participatory research (PAR) and socio ecological systems (SES) approaches.

This is an iterative process where equally valued small steps or larger steps at any given time leads to systems change. The driver of the latter (SES) is to balance human benefits with the protection of the Camargue which in its beauty and perceived wilderness has conflicts and degraded natural and artificial systems.

The belief is that a shared vision and collaborative processes will lead to new knowledge and both collective and individual actions that inform adaptive management practices including better water management approaches.

The spiral generates a diversity of mutual learning experiences that leads to new knowledge that empowers participants to build a pathway toward adaptive and sustainable solutions. This is a generative process that hopefully is scaleable.

The collective experience produces social capital, which is more valuable and fundamental than technologies. It addresses the fears of climate change through growing awareness of a collective experience that recognizes the interests, stakes, skills, constraints, knowledge, and norms, and values of others. Consequently, the end product is, more than technology per se. It is a discovery of appropriate technologies in a good for all spirit (including the welfare of nature).

Adaptive Management Practices in the Camargue

Adaptive governance is a continuous problem-solving process “by which institutional arrangements and ecological knowledge are tested and revised in a dynamic, ongoing, self-organized process of learning by doing”(Plummer and Armitage 2007)

Considered an optimal site for experimentation among wetlands Camargue managers are trying out adaptative management practices that more or less follow the "will" of the Camargue as a dynamic and unstable system by adopting soft engineering practices.

Twenty million m3 (cubic meters) of mud is annually carried downstream by the Rhône. It slowly projects the Camargue into the Mediterranean. One problem with historic containment in the Camargue is that deltas are landforms that are created as sediments flow downstream and are then deposited at the mouth of a river. Seasonal floods typically build up and expand deltas. However, traditional flood-control efforts, such as levees, dams, and 19th century dikes, have blocked the movement of sediment and prevented deltas from regenerating, even during severe flooding events.

Unlike hard engineering approaches (containment by a dike or a dam for example) soft engineering uses ecological principles and practices that have less impact on the natural environment. Soft engineering is also less expensive to implement and maintain. The view is that represents more long-term, sustainable solutions than hard engineering projects.

Some goals of adaptive management in the Camargue include monitoring systems, protecting existing areas, prioritizing the most at risk areas, establishing buffer zones, re-working water abstraction practices, and/or restoring ecosystems and renaturalizing artificial systems.

Management through a network of organizations invite stakeholder participation from resident users and the public, have adopted a more “a let nature take its course attitude as they invest in soft engineering approaches. This includes approaches such as developing monitoring systems for more reactive and quick responses to invasive species or installing wooden fences called Ganivelles to restore a dune, or allowing dikes to deteriorate along with other features of an artificial system.

Methods in the Camargue

STAKEHOLDERS

Climate change adaptation is ... a dynamic social and institutional process (Hinkel et al. 2010).

The Camargue Delta like other wetlands is an organism facing climate changes that have planetary effects.

Stakeholders are local, regional, national, and international interests.

The goal behind bringing people and organizations together using participatory methods is to cooperatively develop viable plans to achieve adaptive and responsive outcomes that build resiliency.

Conservation and preservation of nature and the development of viable food systems are both essential activities that take place in an environment characterized by a range of fresh and saline waters that are changing and willful.

Communicating how to reimagine an ever changing environment to stakeholders in terms of human use and biodiversity protections is a significant challenge.

The greatest challenge to achieving common interests given the uncertainties surrounding climate change is easing the tensions between stakeholders that demand its waters to different degrees.

Converging stresses are felt by stakeholders, who are directly impacted, not only by climate change but by efforts to manage climate change. This influences the sustainability of cooperative processes.

Access to different types of knowledge reduces this stress. Knowledge from stakeholders might be statutory, scientific, experiential from users and from broader interests, technical knowledge, or the social sciences.

Participatory methods require a triadic relationship between government, users, and the general public.

There has been a global shift in awareness of climate change by governments that have expanded policies and treaties to include more climate change factors and adaptive approaches whether it is the use of participatory tools or policing.

Nature has no boundaries. By treaty nations have historically put aside national agendas to especially accommodate migratory birds. The iconic greater flamingos might travel hundreds of miles from the Camargue to destinations such as Africa hundreds of miles depending on the ecological state of spaces within the Camargue system.

How do top down policies or program directives from the EU down to local urban planning affect different stakeholders? Local access to statutory knowledge helps to understand both forces and boundaries from the top down and more inclusive pathways to decision makers.

It helps to understand how decisions behind policies influence local decisions regarding conservation and agriculture that prevent or allow effective actions among different stakeholders.

Among a few examples, the Camargue's national nature reserve is designated by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site. This designation requires certain critiera for cultural and natural landscapes.

European Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) regulations can carry penalties for Camargue farmers that influence their participation when policies introduce restraints on agriculture toward a greener future which might be viewed by farmers as another factor in lower yields.

The French biodiversity office established in 2020. holds a broader range of powers than in the past that include newer regulations regarding policing which may benefit climate change goals but not be well received.

The Ramsar Convention came into force 1975 as an inter-governmental conservation treaty to provide a framework for co-operation for the conservation and wise use of wetland habitats. However, it has not brought adequate support to the formation of management plans. It has had limited success in promoting effective measures toward more effective inclusiveness.

Localized relationships can challenge participatory approaches. For instance, urbanization surrounding the Camargue continues to impose pressure on the coastal site and this requires reaching out to urban planners who may not be as vested in conservation and agricultural goals.

Wetland restoration can meet resistance from local authorities due to issues such as a fear of mosquito explosions, the loss of jobs in the agricultural sector, or perhaps harm to tourism. Along with agricultural practices the latter is a major contributor to the effects of climate change and yet it is a major economy in the delta.

Locally as top-down policies and programs change water managers in the Camargue must contend with new knowledge and changing relationships as well as inadequate budgets.

PAR in the camargue?

Participation benefits from acting together on projects and programs. The Camargue has had a number of successes in this regard.

The Tour du Valet is a private research centre, founded in 1954 and based in the Camargue. It is concerned with the conservation of Mediterranean wetlands and migratory water bird populations, The research center works in close partnership with other organizations following a "Nature-Based Solution (NbS) concept to protect biodiversity and ecosystems given climate changes and to also support sustainable livelihoods.

Part of its mission is to encourage a participatory platform to achieve goals such as developing the best hydrological modeling using simulation tools.

A hydrological simulation tool based on the study of 30 marshes in the Camargue helped to visualise the impacts of different ways of management, for instance to measure the (inputs/outputs of the Mar-O-Sel regarding the salinity of saltmarsh surface and groundwater. Estimates provided insights into the movements of fresh or salt water at different times of the year.

Another Tour du Valet project involved working with private/public interests on a nature restoration project that transformed a former saltworks enterprise into a buffer area to mitigate flood risks as opposed to rebuilding traditional seawalls along with other coastal defense structures along the coastline.

Conflict between hunters and rice farms was successfully addressed by role playing and simulations of effects from different wetland uses on habitat and fauna dynamics.

Given the uncertainties associated with climate change establishing a more sustainable framework for action is a critical task. Areas of conflict surrounding the salinity and flow of water and associated concerns will persist to one degree or another between rice growers, fishermen, hunters, and conservationists, and promoters of tourism.

Some concerns are not going to go away easily if at all. They require a broad knowledge base that incorporates the study of historical, political, environmental, technical, and social factors in the Camargue. For instance, given standing waters in the delta, mosquito abatement is a common concern. historical references have helped explain how agricultural changes in the Camargue have directly contributed to variation in the abundance of both An. hyrcanus and Cx. modestus mosquito populations, with possible consequences for vectorborne diseases. An. hyrcanus is currently considered the main potential malaria vector in the Camargue.

The challenge of climate change in the Camargue requires foresight within sustained and broadening participation. In terms of sustainability, the effects of climate change means it is likely that new conflicts will emerge. For example, it is projected that while climate change may have positive effects on crop production in the North, southern areas could face water shortage and extreme events leading to lower yields, especially in Mediterranean areas (Olesen and Bindi, 2002; Maracchi et al., 2005; Miraglia et al., 2009).

All forms of landscape are crucial to the quality of the citizens’ environment reflecting the diversity of their common cultural and 6 natural heritage and as the foundation of their identity” (Dury 2002).

Limiting the human impact by raising awareness from the largest public possible is also an important activity. The large landscape of the Camargue is located between dense populations which are Montepplier, Nimes, Arles and Marseille as well as the industrial site of Fos-sur-mer. The entire area constitutes the need for participation in actions affecting the Camargue.

One challenge for PAR is building inclusiveness around a phenonmen that is not yet seen or perhaps strongly denied by people who are passive or non-users of the Camargue and/or see themselves as indirectly affected by climate change. This calls for value-oriented methodologies. (This does not exclude tourism as a stakeholder).

In a hypothetical choice experiment directed to the public about the Camargue questions about tree hedges or the iconic value of flamingos uncover values; perhaps on recreational use versus conservation use. Questions might include: how much would the public pay to support their values? Are they passive or active users of the Camargue? How much do respondents value the delta for future generations. Questions such as these provide insights the strength of a sense of place and help identify areas of strong agreement.

Some references have more appeal than others as far as common understanding. There were outbreaks of the West Nile Virus in 1962 and in 2000. These outbreaks were associated with rice standing waters and heavy populations of birds and horses. Climate change can contribute to outbreaks if the change increases over-wintering mosquitos.

The fate of the iconic greater flamingo is another more broadly shared concern. During cold snaps Flamingos that did not migrate to North Africa or elsewhere died of starvation in 1985 and 2012. The deaths occurred in unseasonably frozen ponds just when the flamingos energy demands peaked. The event indicated how vulnerable the birds will be in the face of climate change.

There are many challenges and uncertainties to do with climate change and adequate participation. We have a "wicked problem" otherwise known as a "mess."

There have been positive trends.

Globally pragmatic references to methods for addressing climate change seem more frequent among nations. There are increasingly more participatory references in association with climate change as well.

Successes with PAR in addressing climate change in the Camargue have happened due to enough willingness to engage in a uncertain process by users, residents, private and public interests, and governmental bodies.

What is the lesson to be learned? The ultimate sustainability of cooperative projects and programs will ultimately depend on a new way of looking at deltas and wetlands more as a commons and as a networked system that challenges closed systems of power and concepts of exclusive ownership.

Climate Change is a story of resilency and acceptance of the forces of nature toward cooperative approaches.

The role adaptive management plays in managing vast and vulnerable areas like the Camarague is important to understanding climate change preparation that engages longer term thinking and various options for remediation.

Maintaining relationships with nature and cooperation among groups based on both traditional values and new methods will ultimately determine the success of adaptations to climate change. This has not to date been inclusive enough of vital indigenous interests. This is probably a subject of advocacy which is not well enough represented in participatory research methods.

Finally, the story of the Camargue delta reflects the status of wetlands around the globe in richer and poorer countries. It is a good idea to observe this story as it unfolds. S.G. Crowell

READINGS

The Camargue wetlands, information sheet

Diving Deeper

Adaptive restoration of the former saltworks in Camargue, southern France: CASE STUDY, Climate Adapt, Newsletter.

OECD. (2017). Boosting Disaster Prevention through Innovative Risk Governance: Insights from Austria, France and Switzerland.Series: OECD Reviews of Risk Management Policies., 31.

Europe, C. O. (2017). Landscape dimensions.

Group of Specialists on the European Diploma for Protected Areas. Compilation of Annual Reports, Proceedings from Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats, Strasbourg (2021).

Gardner, Royal C, et al. State of the World's Wetlands and Their Services to People: A Compilation of Recent Analyses, Ramsar Briefing Note No. 7. Gland, Switzerland: Ramsar Convention Secretariat, 2015

Maughan, N. (2015). Mediterranean coastal wetlands dynamics: Forward. Journal of Mediterranean Geography. S

Sylvestre Delmotte, et al. (2012). Combining modeling approaches for participatory integrated assessment of scenarios for agricultural systems: an application to cereal production systems in Camargue, South of France. Proceedings from European IFSA Symposium:Producing and reproducing farming systems. New modes of organisation for sustainable food systems of tomorrow, Vienna. statement, T. F. O. O. B. M. Office of Biodiversity.

Ernoul, L. et al. (2021). Context in Landscape Planning: Improving Conservation Outcomes by Identifying Social Values for a Flagship Species. Sustainability, 13, 6827.

Guehlstorf, N., & Martinez, A. (2019). State Conservation Efforts of Seasonal Wetlands along the Mississippi River. Conservation & Society, 17(1), 73-83.

Nigel G. Taylor, et al. (2021). The future for Mediterranean wetlands: 50 key issues and 50 important conservation research questions. Regional Environmental Change, 21(31).

Arcaute-gevrey. (2018). The restoration of the former saltworks in the Camargue: a Nature-Based Solution to adapt to sea-level rise. Tour du Valat Newsletter.

Alice Newton, et al. (2020). Anthroppogenic, Direct Pressures on Coastal Wetlands. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution: Conservation and Restoration Ecology. Johnston, R. J. (2018).

Ecosystem services. Encyclopedia Britannica.